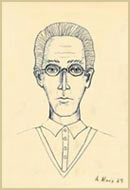

Yannis Philaretos (1935-1999) Drawing by Alfred Hoos

Philaretos’s Interview (extract from a much longer biographical interview)

I’m not completely clear. Isn’t what you are referring to …’sacred art’, art with a sacred aim, art that wants to lead you to the sacred?

Well, to produce sacred art it is not enough to have a sacred aim, you must operate within a sacred tradition. This, according to Hoos’s viewpoint was the tragedy of the abstract expressionists – this is why he calls the story of Jackson Pollock ‘tragical’ – that is in a sense paradigmatic of modern man’s tragedy: although they did good work in subverting the forms of a world that had been drained of meaning, destroying not only naturalistic representation but formal abstraction, although they essentially yearned for a profound vision, they couldn’t find it because they weren’t looking at the right place. There is this story of the Mullah Nasr-Eddin that Hoos liked to tell: “Nasr-Eddin is searching under a lamp-post, outside his house. A neighbor asks him what he’s looking for and Nasr-Eddin says he lost his keys. The neighbor: ‘Did you lose them out there, Mullah?’ ‘No,’ the Mullah replies, ‘in my house.’ ‘Then why are you looking for them out here,’ asks the neighbor. ‘Because here there is more light,’ replies the Mullah.” This, to Hoos, is the modern artist’s situation: they are looking where they know how to look – not where the truth really lies.

I still can’t see how Hoos saw the abstract expressionists as ‘tragical’ figures. After all, they acquired fame, money, critical appraisal even…

Oh, Hoos didn’t give a damn for any of these things. Also, if you look at the lives of Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko, what you see is people who are basically unhappy, unfulfilled. The first a hopelessalcoholic, – look at the mess he made of his life, look at his death!-, the second basically a very sad person, and the third an introverted depressive who took his own life. I met Rothko, you know.

Oh, Hoos didn’t give a damn for any of these things. Also, if you look at the lives of Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko, what you see is people who are basically unhappy, unfulfilled. The first a hopelessalcoholic, – look at the mess he made of his life, look at his death!-, the second basically a very sad person, and the third an introverted depressive who took his own life. I met Rothko, you know.

Why, tell me about it!

He came briefly in London, when the hall with his works opened at the Tate. The three of us, Hoos, Rothko and I had dinner one evening in a small Indian restaurant in Kensington.

What was he like?

A somber man. Hoos, by contrast, was lively, outgoing, radiating a wonderful sense of energy. Rothko was not very communicative; he didn’t speak much, he was listening with great interest, it seemed to me, to Hoos. Hoos gave him his pamphlets and briefly expounded some of his main theses, mostly the Audience and the Anthropology principles. Rothko seemed very responsive to that, he told us about how he refused a very attractive order by some super-chic restaurant in New York that wanted to have his paintings on their walls. He said that he declined the offer because ‘the clientele consisted solely of very rich people’.

A somber man. Hoos, by contrast, was lively, outgoing, radiating a wonderful sense of energy. Rothko was not very communicative; he didn’t speak much, he was listening with great interest, it seemed to me, to Hoos. Hoos gave him his pamphlets and briefly expounded some of his main theses, mostly the Audience and the Anthropology principles. Rothko seemed very responsive to that, he told us about how he refused a very attractive order by some super-chic restaurant in New York that wanted to have his paintings on their walls. He said that he declined the offer because ‘the clientele consisted solely of very rich people’.

Well, I can’t imagine Rothkos hanging at hamburger joints either!

To get back to my point – Hoos’s point, really – about these people. He chooses to tell the stories of the lives of those three, Pollock, Newman and Rothko, to illustrate certain very concrete ideas. Pollock, I have said, was at first the destroyer, but also the one of the three who is most childlike. And like a child often does (or an adolescent, too) he disregards every rule in the book, wants to inhabit a present totally unburdened by any sense of tradition. That comes out quite well in The Tragical History, not least with the use of the child-like form of shadow-puppetry. In the Newman play…

To get back to my point – Hoos’s point, really – about these people. He chooses to tell the stories of the lives of those three, Pollock, Newman and Rothko, to illustrate certain very concrete ideas. Pollock, I have said, was at first the destroyer, but also the one of the three who is most childlike. And like a child often does (or an adolescent, too) he disregards every rule in the book, wants to inhabit a present totally unburdened by any sense of tradition. That comes out quite well in The Tragical History, not least with the use of the child-like form of shadow-puppetry. In the Newman play…

May I interrupt: are you going to perform the full trilogy, the full Tragedy of the Abstract Expressionists?

No, alas not, I didn’t have the time or the money to set it up now. We are doing The Tragical History of Jackson Pollock for starters, and next year I hope I will do the full show.

Still, tell me a few things about the other two plays, the ones about Newman and Rothko.

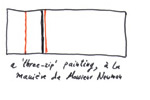

To Hoos, Newman was the more positive of the three, perhaps because of the strength and clarity of his critical writings. Newman wrote of the need for a positive, new vision. And Hoos saw the ‘zips’, the vertical lines that constitute the most characteristic parts of his later paintings, really as openings to the Beyond.

To Hoos, Newman was the more positive of the three, perhaps because of the strength and clarity of his critical writings. Newman wrote of the need for a positive, new vision. And Hoos saw the ‘zips’, the vertical lines that constitute the most characteristic parts of his later paintings, really as openings to the Beyond.

There is a progress, from the metaphysical viewpoint. Abstract expressionism begins with Pollock and his statement that the “modern artist must express his feelings”. Then, with ‘Barney’ – as Hoos called Barnett Newman – we move from the internal (feelings) to the transcendental (the world behind the ‘zip’). Then comes Rothko, who very definitely wants to make a strong metaphysical statement. To no avail of course.

Why ‘of course’?

No man who ends his life as Rothko did is fit to lead others to a strong positive vision.

But is it fair to judge an artist’s work from his life?

It was Hoos’s belief – and it is mine too – that you can. On this, he used to refer to the evangelical “ye shall know the tree from its fruit”.

It was Hoos’s belief – and it is mine too – that you can. On this, he used to refer to the evangelical “ye shall know the tree from its fruit”.

Tell me a few things about Hoos’s way of ‘dramatizing’ the story of Pollock – if ‘dramatizing’ is the right word.

I don’t think it is – Hoos’s. He wouldn’t have liked it anyway. He would probably have said ‘narrating’, he was all for the epic view of the theatre, theatre as a tool for storytelling. That’s why he always started to write a story, any story, in fairytale form. You know, ‘once upon a time there was a little boy, called Jackson Paul Pollock…’

| 1935 | 6th of September, Yannis Philaretos (YP) is born in Athens, son of industrialist Constantinos and Hermione Philaretos, nee Delipetros. |

| 1942 | His family moves to Alexandria, Egypt, where YP attends the French Lycee. |

| 1953 | YP enrolls at Cambridge University, to study Classics. |

| 1956 | YP returns to Athens and joins a friend’s import-export firm. He begins to write. |

| 1960 | Resigns from his post and settles in the family house in Kifisia, to the north of Athens. |

| 1961-1964 | Writes the three works of fiction to which he owes his miniscule literary reputation, the novellas Mustapha Pasha Interlude, Christina’s World andOld Athenians. Begins the (unfinished) novel The Chronicle of the Tzimas Family. |

| 1963 | Meets the Greek poet and essayist Zissimos Lorentzatos after reading his seminal essay “The Lost Center”. |

| 1965 | August. Meets Alfred Hoos, in the house of Karaghiozis player Sotiris Spatharis. |

| 1965-1967 | Spends almost two years travelling around Greece, the last months of which on Mt. Athos, ‘the Holy Mountain’, an all-male monastic community in the north of Greece. |

| 1969 | Goes to London, to assist Alfred Hoos in the preparation of The History of Western Art, from Narthex to pissoir. After Hoos’s death, later that year, Philaretos returns to Athens. |

| 1971 | Writes the monograph Alfred Hoos and his Project for the Future of the Arts. |

| 1972 | He founds and is named president of the ill-famed Institute for Cultural Regeneration. The ‘Institute’ is exclusively funded by the Ministry of Culture of the so-called ‘National Government’, i.e. the military junta that rules the country from April 1967 to July 1974. |

| 1973 | In March, he is named the junta’s Deputy Minister of Culture. He attempts to apply an extensive program of ‘cultural regeneration’, involving the performance of the ‘heroic’ plays of Karaghiozis all over Greece. His proclamation of the program, during a press conference, is interpreted by the democratic opposition to the dictatorship as a call for cultural censorship of the most repressive kind – a charge YP never accepted. |

| 1973 | November. When a new military putsch overtakes the ruling junta and installs a new one in its place, Philaretos is placed under house arrest for a week and then is ‘encouraged to’ (read: forced to) leave the country. |

| 1974-1981 | Lives for relatively short periods in Rome, Florence, Paris, London, Venice, the Alpine village of Sils Maria. Devotes his time ‘to the study of world history’ (an expression also used by Hoos to describe his earlier life) and writes a series of (mostly unpublished) monographs on the history of art. |

| 1982-1989 | Settles in the Republic of San Lorenzo, where he is employed as an advisor to the ‘National Government’, on cultural matters. There too, he masterminds an ambitious program of ‘cultural regeneration’. |

| 1989 | October. He escapes the country, when the democratic opposition overthrows the ‘National Gorvernment’ |

| 1989 | In December, he arrives in London to arrange for the publication of Hoos’sComplete Works. After some years of troubles, the project falls through, for lack of funding. Meanwhile, Philaretos earns his living as a translator. |

| 1994 | Returns to Greece. Settles in a small house in the centre of Athens. Writes, but does not publish, a short book on his much criticized collaboration with the military junta. |

| 1998 | Receives a private grant to complete and perform The Tragical History of Jackson Pollock, Abstract Expressionist, as closely as possible to the original conception of Alfred Hoos – based on Hoos’s original drawings for the puppets, now completed by YP. |

| 1999 | January 22-27. While rehearsing The Tragical History of Jackson Pollock, Abstract Expressionist, meets the present author for a series of interviews on his life, work and ideas. |

| 1999 | 1st of February. The Tragical History is given its first performance in the Zoumboulakis Galleries, Athens. On the afternoon of the next day, a bomb explodes outside the gallery, as Philaretos is entering to prepare for the evening’s performance. He is instantly killed. The militant organization ‘Revolutionary Nucleus for Cultural Action’ takes the responsibility for the act, claiming not to have intended the death of Philaretos – just his punishment for his collaboration with the junta. To this day, no arrest has been made. |